Welcome to our exciting new blog series: Understanding Search Warrants. This article is about the search warrant document. In these posts, we’ll take a close look at search warrants and how they work. We’ll start with the basics, explaining what a search warrant is and what’s inside it. Then, we’ll talk about different types of search warrants: those for houses, cars, people, and technology! We’ll also go over how search warrants are used in cases of fraud and why it’s important that warrants are specific. And that’s not all! In our ‘Search Warrant Special Procedures’ advanced series, we’ll talk about more complex topics like the rules for searching, serving warrants at night, sealing search results, and using drones in search warrants. Join us as we discover the interesting mix of laws, technology, and practices that make up the world of search warrants.

Getting a search warrant might seem like an easy answer for police officers dealing with tricky search and seizure situations. But, it’s not that simple. Officers can’t just “get” a warrant – they must ask for one. And asking for a warrant isn’t easy. Crafting a search warrant can be a tough and time-consuming task, even for experienced investigators.

Before we start, let’s break down what we’ll be talking about. There are two big parts to this topic. The first part is about what a search warrant is and what it allows law enforcement officers to do. The second part is about what the warrant should look like and what it should say. This includes the details in the warrant itself and the written statement that comes with it. Some of these details might seem small, but they’re very important. If they’re not right, the warrant might not be valid.

A warrant packet is comprised of two parts: the Search Warrant and the Affidavit.

A search warrant is simply a court order and must contain the information that is necessary to constitute an enforceable judicial command, plus certain information required by statute.

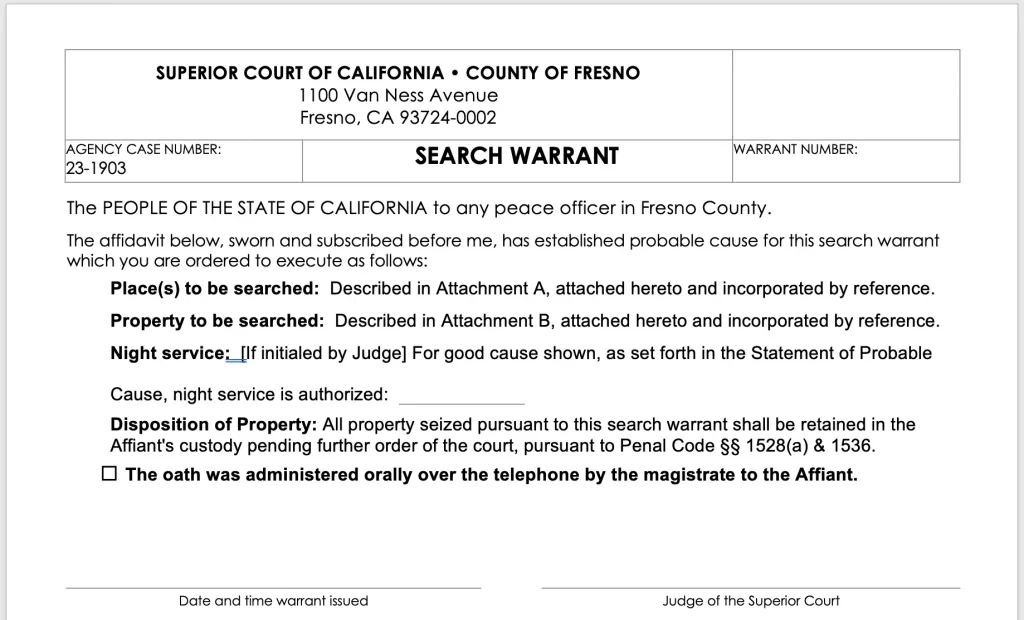

Most criminal codes prescribe a minimum requirement for the form and flow of a search warrant document. The Search Warrant is comprised of six components: the heading, affiant identity and jurat, search location, items to be seized, evidence disposition, and warrant authority & criminal violation. The physical appearance of the warrant is 100% a matter of tradition; State seals, fonts, and the structure of the document are simply a means of utility and making the document look how the Court prefers.

The Heading: The heading of the document accomplishes two goals: identify the issuing court and the County of issuance. The county that is listed in the header must be the same as the county in which the issuing judge sits. For example, if the warrant was issued by a judge in Fresno County, the warrant must be directed to “any peace officer in the County of Fresno.” This requirement does not prevent a judge from issuing a warrant to search a person, place, or thing located in another county or in another State.

Search location(s): A search warrant authorizes the search of places, items, records and people. Each warrant will have a section where the location to be searched is described in detail. For residential search warrants the warrant will contain a “legal” description of the residence that identifies the residence with enough detail to avoid confusion with neighboring houses.

Items to be seized: The items to be seized section is usually a list of those specific items that the Affiant knows will constitute evidence of the crime. The items must be described “with particularity” specifying what will be seized. Vague descriptions can result in severance and the evidence being tossed out. More on particularity below.

Disposition of Evidence: The warrant must include instructions as to what the officers must do with any evidence they seize. Typically, the warrant will command the affiant to bring the evidence to the judge and the affiant must retain the evidence pending further order of the court.

Note: Officers hold the evidence on behalf of the court; they may not transfer possession of it to any other person or agency without further court order.

Warrant Authority & Criminal Violation: Most criminal codes specify that search warrants may be issued for certain types of evidence, depending on the crime under investigation being a felony or misdemeanor. Some States only have a few authorities for the issuance of a warrant while California has 20! Officers will likely see authorities like:

States like California have additional authorities addressing issues like firearm seizures, DUI blood draws, GPS trackers, and vehicle data.

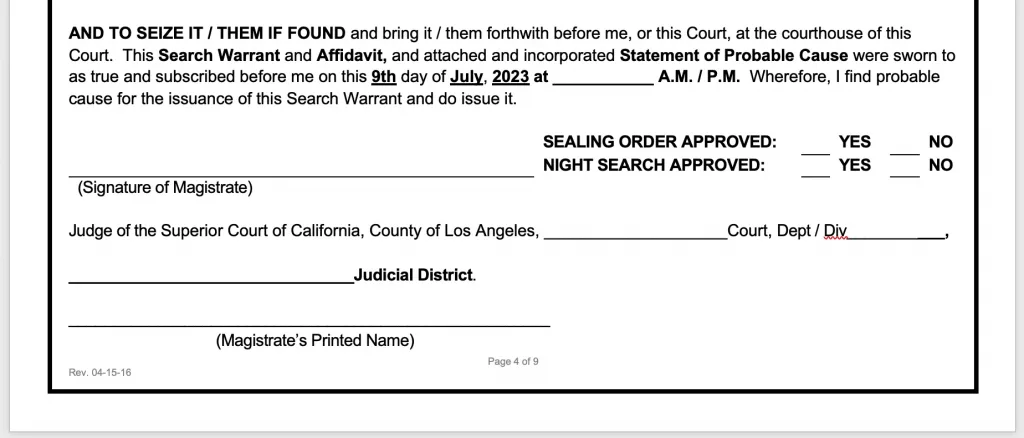

The execution of a search warrant may require special procedures such as conducting the search at night, sealing the affidavit, or employing a no-knock entry method. These special procedures are handled differently from county to county and sometimes judge to judge. Warrants for online records would usually benefit from a non-disclosure order, an authenticity of record order and a target notification delay order. But where do these go? As long as the judge has a place to sign for their authorization, they can go anywhere in the document. These special procedures and court orders are usually found on the search warrant itself, within the Attachments, or as stand-alone documents. Modern warrants usually incorporate the special procedures within the warrant to streamline the process. A stand-alone court order requires its own affidavit which can make the warrant application and review process tedious. Modern warrants typical contain the text below followed by the procedure or order:

Authorization to implement special procedure(s): The Affidavit filed herewith has demonstrated legal justification for the implementation of the following special procedures which shall be employed by the officers who execute this warrant:

A search warrant affidavit is essentially the story behind the warrant. The document outlines the facts of the case and why the Affiant knows evidence will be found at the location they are requesting to search. The document consists of:

(1) Statement of probable cause.

(2) Descriptions of the place to be searched and the evidence to be seized.

(3) Justification for implementing special procedures (if any).

(4) Other information required by law.

Crafting the statement of probable cause is often the most challenging and time-consuming aspect of the process. The affiant must convince the judge that it is likely the evidence they’re seeking exists, that it’s currently at the location they want to search, and that it will still be there when the search is carried out.

Starting with organizing the facts, the affiant should begin by writing down the key details that will establish probable cause. This approach reduces the likelihood of missing out on important information. While it’s not about crafting a prize-winning essay, the affiant should arrange the facts in a logical order, especially in complicated cases.

Moving on to the editing and simplifying stage, the statement of probable cause doesn’t need to include every single detail officers have discovered about the crime or the suspect. Rather, it should provide the judge with enough information, both positive and negative, to make a sensible determination of probable cause.

Common Mistake: It is common to see inexperienced officers simply use their crime report as a probable cause statement. Crime reports are often filled with cop jargon like S-Watkins or V-Stevenson identifying Watkins as a suspect and Stevenson as victim. Crime reports frequently contain details that, while important to the prosecution of the case, are irrelevant to search warrant application.

The Affiant: Normally, the affiant is the investigator who is most directly involved in the investigation and most knowledgeable about the facts outlined in the affidavit. While it’s common for peace officers to be affiants, anyone, such as a prosecutor or an informant, can assume this role.

The affidavit should include a statement about the affiant’s training and experience specific to the investigation, also known as the “Hero Sheet”. Including an officer’s curriculum vitae (CV) often clutters the document with irrelevant information; it’s great that you went to homicide school but what does that have to do with this stolen lawn mower case? It’s important to note that the affiant doesn’t need to have been recognized as an expert witness in court to share an opinion.

Descriptive Information: The affidavit needs to provide details about two key things:

This information is not only required on the warrant but also crucially needs to be in the affidavit. That’s because the affiant has to affirm that these details are accurate, and only the information within the affidavit is covered by this sworn promise.

Many search warrant documents use an attachment system for clarify and brevity. For example, the warrant will have an Attachment A that details the location to be searched and Attachment B that details the things to be seized. The Affidavit will reference these attachments to reduce redundancy. It is important to have both the search warrant and affidavit reference attachments as “attached hereto and incorporated by reference.”

Special Procedure Justification: If the affiant requests special procedures like night service, the affidavit must contain the facts to justify the request.

The Oath: The affiant must sign the affidavit under oath. The affidavit will often contain text similar to: “I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true.” The affiant swears that

Affiants should not claim that their information proves probable cause; this is a legal judgment that only a judge can make. Also, affiants shouldn’t state that they “believe” they have probable cause. As emphasized in the court case of People v. Leonard, warrants should be granted based on facts, not personal beliefs.

Exhibits & Attachments: The affiants probable cause may partially rely on information found in other documents like police reports, fingerprint or DNA reports, or photographs. In complex cases, link charts are especially helpful to the judge to reference. If an affiant wants to use other documents to supplement their affidavit, they can be attached and incorporated by reference. If the warrant format uses attachments to specify the location to be searched and items to be seized, it is recommended to refer to the extra documents as exhibits or vice versa.

The question has arisen whether officers who are investigating a misdemeanor can obtain a warrant to search for evidence. As discussed in the Warrant Authority section above, some states have restrictions limiting warrants for felonies, some do not. It is arguable that a judge could do so because the statute does not say that judges are prohibited from issuing warrants for other types of evidence; it is merely a permissive statute, and the distinction between prohibitive and permissive statutes has long been recognized by the courts. Furthermore, evidence that was obtained by means of a warrant that was constitutionally valid cannot be suppressed on grounds that the warrant violated a state statute. As a practical matter, however, judges may be unwilling to issue warrants on Misdemeanor violations.

I wrote a warrant, now what?

Depending on your Court and Prosecutors Office preference, it is common to submit the warrant to the District Attorney/Prosecutor for review prior to submitting it to the Judge. Some Counties require it, other don’t, and others still refuse to provide insight into search warrants to maintain their impartiality. A prosecutor, preferably one who knows the law of search and seizure relevant to the investigation, should review an affidavit if there are legal issues with which the affiant is unfamiliar or uncertain. A review is also recommended if the existence of probable cause is a close question. This is because a prosecutor’s approval is a circumstance that the courts will consider in determining whether the good faith rule applies.

If the prosecutor gives the thumbs up, you are off to the Judge!

Local court procedure determines the proper method to submit a warrant for review; some Courts require the Affiant to physically come to their chambers while others have eWarrant systems using emailing or digital upload. The Judge will review the document to consider the facts and either approve, deny or reject the document for a rework. If approved, you move on to executing the warrant, preparing an inventory and returning the warrant to the court; more on that in future posts.

Sounds complicated, right? No worries, Warrant Builder makes writing search warrants a snap. Warrant Builder properly formats your warrants for you, in the style that your court prefers, so you can focus on your probable cause statement. Get started writing warrants today!

Destin is a law enforcement professional and Digital Forensic Analyst with over 20 years experience. As the co-creator and CEO of Warrant Builder, Destin has unique insights into search warrants and online investigations. You can follow him on LinkedIn